Black Lives Matter in Japan

In June, I found myself in a police station in Kyoto with two strangers I met on Facebook. We sat in the grey conference room of the Higashiyama police station with the director of the riot control unit. To submit a request to hold a Black Lives Matter march in Kyoto, one spends an hour and a half to go through thirty pages of bureaucratic paperwork. This meeting reminded me of all the things I loathe about Japan. The police officer, a man in his early 30s, refused to look Mari or me in the eyes—because we were women, or because he thought we were foreigners, or both. We watched the officer call three different police wards to decide if umbrellas should be allowed at our march. In the end, he decided that the risk of someone having their eye poked by an umbrella was too high to condone umbrella usage. The slow and laborious process of organizing a demonstration in Japan contrasted what I had seen of the American protests on my social media feeds, fueled with passion and urgency.

Mari, Kent, and I had connected on Facebook after the Black Lives Matter march in Osaka. The march, one of the first in Japan, drew 2,000 people and energized a new wave of activism in Japan. I attended the Osaka march with a group of school teachers who taught at an international school in Kobe. Like the rest of the attendees at the march, the school teachers were mostly Americans, outraged by the senseless killings of Black Americans and by the brutal displays of police violence. The march in Osaka was the first protest I had ever been to, and it introduced me to a segment of Japanese society I had never seen. This was the first time I’d witnessed a large demonstration in Japan, and also my first time I’d seen so many hafus or mixed-race people, like me, in one place, or heard race spoken about so explicitly in Japan.

In the United States, the brutal confrontation of police brutality and racial injustice galvanized protesters and awakened many Americans to their complicity in systems of white supremacy. But in Japan, where a myth of racial homogeneity persists, protesters struggle to draw support from a wider Japanese audience.

Organizing in Japan happened mostly on Facebook -- it was clumsy and scattered, but vitalizing. I found a post by Mari asking if anyone in Kyoto would be interested in organizing a march, and after a couple of calls the group had grown from three people to six admins. We researched how to organize a demonstration in Kyoto, strategized on how to get the word out, and tried to keep track of all the small details: signs, press releases, and making materials accessible in both Japanese and English. We had dozens of Google docs running, LINE group chats for volunteer outreach, and multiple social media accounts running to spread the word. In the Osaka march, the march drew a mainly international crowd, so we tried to think of how we could draw more native Japanese into the movement.

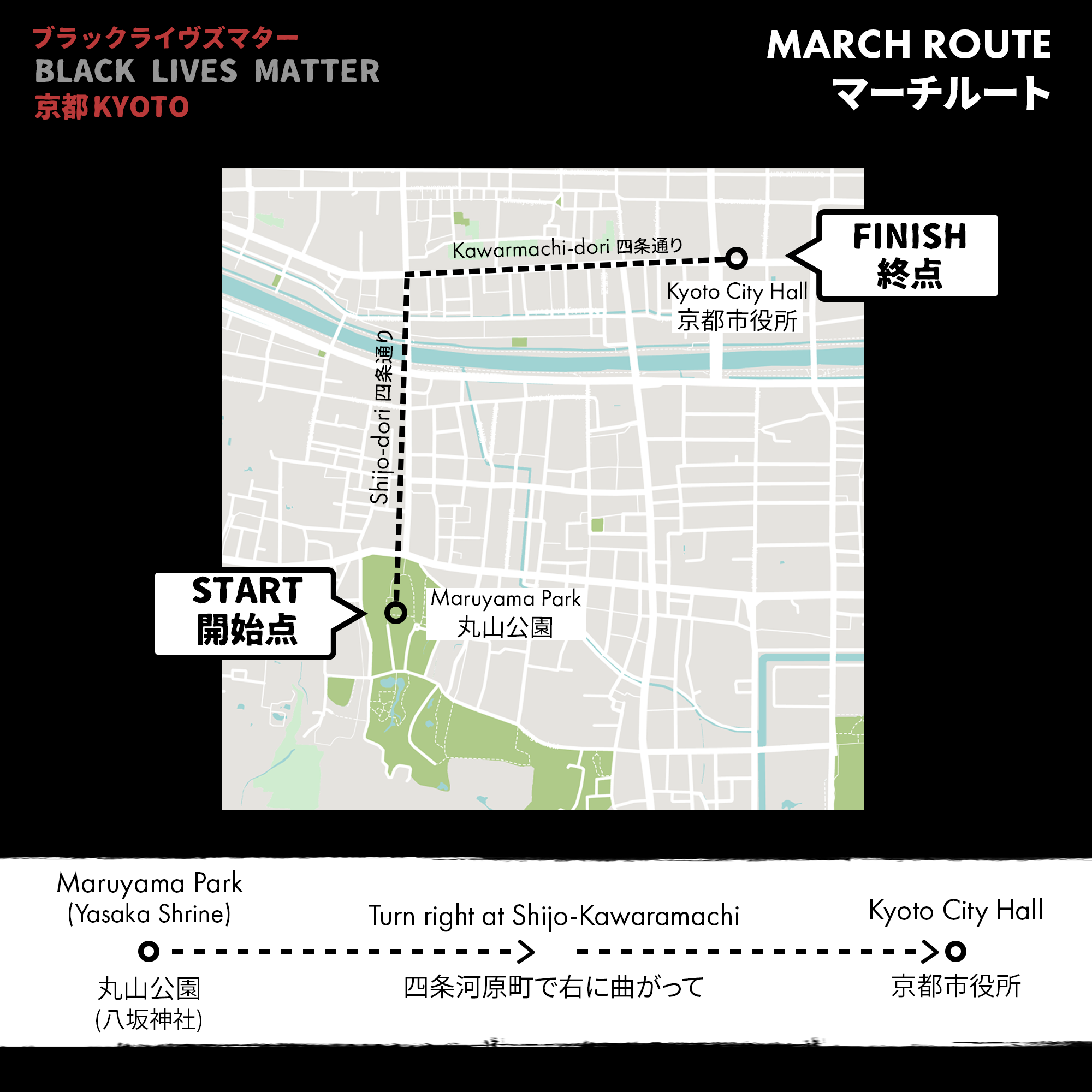

Our police-approved march path.

Our walk route graphic, created by Sachi Mulkey.

Throughout this process, we kept going back to one central question: why is Black Lives Matter relevant in Japan? For us, it seemed like a simple answer – the movement is a plea for basic human rights. But criticisms we often saw on Twitter included: “why protests now, during Corona?” and “why in Japan, if the police brutality is occurring in the United States?”

As we continued to organize, we struggled to contextualize the BLM movement for Japan. When NHK, Japan’s national broadcaster, attempted to cover Black Lives Matter protests and the murder of George Floyd, it produced a crude cartoon caricature depicting Black Americans rioting in front of a car engulfed in flames. 1 The main narrator, a Black man with huge muscles and veins, explains to viewers the justification for the protests:

The reason why we are so angry is the gap in wealth between blacks and whites! Yes, whites, by average, have seven times more wealth than blacks! Ha, here comes the spread of the new coronavirus! Oh, I ask you a question: how many blacks were laid off or had their work hours cut [due to the coronavirus]?

Okiyoshi Takeda, a professor at Aoyama Gakuin University in Tokyo, argues that the NHK video exhibits a wider issue of structural racism in Japan. The clip portrayed the death of George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter protests in the U.S. “as an equal conflict between oppressor and oppressed… render(ing) the causes of racism obscure.” In covering the protests, NHK never mentioned the historical roots of systemic racism. This omission reflects a trend in the Japanese media, which “tends to ignore the inequalities between the majority and minorities,” Takeda writes, and “seldom takes notes of the comparative advantages that ethnic Japanese people in Japan enjoy over ethnic Koreans, Ainu, burakumin, Japanese-Brazilians and other minorities.”

The dominant narrative in Japan is that racism is a uniquely western issue. The Osaka march, however, suggested an entirely different story. Even within our group of administrators in Kyoto, our leaders were members of a Black diaspora living in Japan, other ethnic minorities in Japan, mixed-race individuals, and Asian Americans -- people who do not fit into the idea of one dominant race.

Kent, one of our main admins for BLM Kyoto, is ethnically Korean. Prior to BLM, activism was not something he was familiar with, nor was he heavily involved in anti-racist activity in Japan. But an experience in early June changed him. Kent was walking in Osaka when he encountered a restaurant named after the “k-word.” The Japanese word translates loosely to “Black boy,” but has developed into a slang term with similar connotations to the n-word. He took a picture of the restaurant, posting it to his Facebook.

ショックで暫く立ち竦んでしまったのです。

多分無知なだけなんでしょうが。。。

時間がある時お話に行こうと思っています。。

I was so shocked I caught myself standing there for a while.

Maybe it’s just ignorance...

When I have time, I’m thinking of going in to speak with them.

Kent says he quickly went into a social media hole on the origins of the k-word and anti- Blackness in Japan, and eventually found the Black Lives Matter Kansai Facebook group.

For him, the confrontation of such deliberate racism, gone undetected and displayed so casually on the street, invigorated him to attend a march in Osaka and help organize the march in Kyoto.

For Kent, who is ethnically Korean but grew up in Japan, the presence of systemic racism and exclusion is not entirely unfamiliar. Under the guise of maintaining a homogenous nation, Japan continues to ignore the deep-rooted history of discrimination towards minority groups. Ethnic Koreans, commonly referred to as Zainichi Koreans, are the descendants of colonial-era Korean migrants to Japan. The literal translation of Zainichi is “living in Japan,” which sociologist John Lie explains is “an inevitable inflection of its impermanence.” Despite living in Japan for two or three generations, Zainichi Koreans remain outcasts in Japanese society. Never receiving Japanese citizenship, Zainichi Koreans live with a special permanent residence status, which was granted under a 1965 treaty between Japan and South Korea. Under this law, they are afforded rights and privileges comparable to a citizen, but are unable to vote.

Japan has struggled to navigate the racial diversity that accompanies globalization. No longer a secluded island nation, Japan’s desire to globalize and westernize following World War II counteracts Japan’s historic tendencies to value racial homogeneity and strong nationalism. In her study of hafu Japanese university students, Shima Yoshida theorized that “conflict arises when confronted with the values particular to globalization, those of ‘cosmopolitanism’ and diversity” in a country such as Japan where “homogeneity in ethnicity is maintained as the ideal.”

In recent years, the experience of multi-racial Japanese people has garnered more attention in the Japanese media. Among the most popular of hafu, or half-Japanese, celebrities in Japan is tennis champion Naomi Osaka, who has made great waves in the reconfiguration of “Japaneseness.”

Naomi Osaka in front of Yasaka Jinja, the starting point for our march in Kyoto. (photo from Osaka’s Twitter, @naomiosaka)

Osaka, who grew up in the United States to a Haitian father and a Japanese mother, has endured much racism and criticism for her physical appearance. Before the 2020 Olympics, her citizenship choice was a major topic of Japanese speculation. Dual citizenship is not allowed in Japan, so in order to secure Osaka for the Japanese team, she had to renounce her American citizenship and become exclusively Japanese. To this, many criticized her inability to speak Japanese, and suggested that her Haitian-Japanese appearance should prevent her from acting as a representative of Japan, since it is not reflective of the majority of Japan. Osaka is a part of a group of hafu athletes who have been considered “borderless elite athletes,” as sociologist Naoki Chiba puts it—people of mixed Japanese backgrounds are rejected by Japanese society for their “impure blood” yet also welcomed for their athletic ability.

Osaka’s rise in popularity was closely observed by many Japanese people, because unlike other hafus who had reached mainstream popularity in the past, Osaka was Black, and never hesitated to call out racism or defend her Blackness. In Japan, Western-centric beauty standards prevail: skin bleaching remains relatively popular, and the daily makeup routines of many young women include gluing their eyelids to get rid of the monolid. This discriminatory preference is clearly reflected in media representation as well; the “majority of hafu media figures tend to be of a Japanese/Western national background (with the nationality “American” ranking the highest for Western countries) and a Japanese/White ethnicity.”

Naomi Osaka’s career has been replete with racism, as she has been forced to battle vicious comments about her Blackness. In late 2019, a Japanese comedy duo commented that Osaka should “pick up some bleach” after appearing too “sunburnt” during a competition. Osaka retorted in a series of tweets, causing national headlines and prompting a public apology from the duo. On top of being Japan’s best tennis player, Osaka has been tasked with becoming a representative of Blackness and multiracial heritage in Japan.

Osaka City BLM March. (Photo: Jasmine Cowen)

Osaka city’s Black Lives Matter march received huge publicity after Naomi Osaka retweeted the march poster. Before Naomi Osaka’s tweet, information on the march circulated among small circles in Kansai, but remained undetected by a larger Japanese audience. Naomi Osaka’s fearless and unwavering support of Black Lives Matter has widened the movement’s reach in Japan, but not without the expense of attacks at Osaka, calling her “reckless” and accusing her of “supporting terrorist activity” during a pandemic. In Japan, where issues of racial inequalities are usually connected to a violent imperial history that many would like to forget, conversations of race have become incredibly taboo. For Osaka, an already controversial figure, to call out racism in Japan was seen by right-wing nationalists as an unwelcome act of resistance.

From their conception, solidarity marches in Japan fundamentally differed from Black Lives Matter demonstrations in the United States. In Japan, foreigners are not legally protected when protesting against the government. In 1978, Ronald McLean, an American national, was refused a visa renewal partly for his involvement in the Japanese anti-Vietnam war movement. The McLean case established that ‘non-Japanese have constitutional rights that may be subject to both statutory limitations and administrative discretion.” The worrying precedent of the McLean case, combined with the tightening restrictions on foreign nationals due to Coronavirus encouraged organizers and participants to take every precaution to avoid legal trouble. Organizers had to cautiously curate the appropriate language and signs for the marches, shifting away from messages condemning police brutality and towards interracial solidarity.

The marches in June did not go unnoticed. In Japan, where social activism is generally frowned upon, our march crowds, which would be considered at best “modest” in the United States drew media attention and expanded momentum. With more marches popping up from Tokyo to Fukuoka, major media outlets like NHK revisited segments on racial injustice, this time trying to include more Black voices and more deeply explain the roots of racial inequality in American history. Our march in Kyoto was covered in the local newspaper, and an article on the Black Lives Matter movement in Japan by Motoko Rich and Hikari Hida was printed on the front page of the International Edition of The New York Times.

The Japan that I saw during our Black Lives Matter march was not the Japan I had known growing up. I found myself surrounded by anti-Nuclear peace activists, other people of mixed Japanese heritage, immigrants to Japan from all over the world. Our project to bring a conversation on institutional racism to Japan felt truly shared.

We were energized by the attention the movement seemed to be getting, but the outlook was still bleak. The Times article—entitled “In Japan, the Message of Anti-Racism Protests Fails to Hit Home”—stung. It was true. We had felt so optimistic when our peaceful demonstration in Kyoto had drawn 1,000 people when we had only expected 120. After the march, organizers throughout Japan asked each other: how will we reach a broad audience and create a conversation on institutional racism?

Despite our energy, it became clear that we had failed to sustain conversations between Japanese natives and the international community. Marches throughout Japan have gathered momentum to confront anti-Blackness and racism in Japan, but the process of transitioning to a more sustainable movement, one which could provide lasting change, remains unclear.

To reach a larger Japanese audience, some activists believe the momentum from the marches in June will provide an entryway into deeper exploration of racial justice in Japan. The larger Black Lives Matter chapters in Tokyo and Osaka have worked towards goals of educating Japanese people on how anti-Blackness, colorism, and cultural appropriation prevails in unconscious yet violent ways. Throughout Kansai, multiple restaurants can be found named after the derogatory “k-word,” black face continues to be performed regularly by comedians, and portrayals of Black people on Japanese media remains to be hyper-sexualized and overly aggressive, often reflecting racist tropes originally created in the West.

Within the Black Lives Matter Japan movement, however, a separate faction believes it should remain focused on educating Japanese people on police violence and the deepening racial injustice in the United States, aiming to become a movement in solidarity with American protesters. For other organizers, shifting the focus away from American police brutality would undermine the efforts of American demonstrators who are facing violent police opposition on a daily basis.

As the movement in Japan stands as a crossroads, Black Lives Matter chapters throughout Japan continue to work on how we can foster an understanding of racial injustice through education, support the Black Lives Matter movement on a global scale, and create interracial solidarity for change. Japan’s xenophobic history poses distinct obstacles to growing anti-racist ideas, but the movement is growing, and Japan is beginning to face its own racism.

sources: Chiba, Naoki, et al. “GLOBALIZATION, NATURALIZATION AND IDENTITY: The Case of Borderless Elite Athletes in Japan.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport, vol. 36, no. 2, June 2001, pp. 203–221, doi:10.1177/101269001036002005.

“Japanese Comedians Apologize for Racist Joke about Naomi Osaka Needing 'Bleach',” September 26, 2019. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2019/09/26/national/social-issues/ japanese-comedy-duo-apologizes-naomi-osaka-needs-bleach-quip/.

Jones, Colin. “Schizophrenic Constitution leaves foreigners’ rights mired in confusion,” November 1, 2015. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/community/2011/11/01/general/schizophrenic-constitution-leaves- foreigners-rights-mired-in-confusion/.

Lie, John. Zainichi (Koreans in Japan): Diasporic nationalism and postcolonial identity. Vol. 8. Univ of California Press, 2008

Miyazaki, Shigeki. "The Political Rights of Aliens in Japan and Compulsory Deportation." Law Japan 12 (1979): 82.

Takeda, Okiyoshi. “NHK and ‘Black Lives Matter’: Structural Racism in Japan.” The Asia Pacific Journal , Japan Focus, 18, no. 18 (2020).

Yoshida, Shima. Being hafu (biethnic Japanese) in Japan: Through the eyes of the Japanese media, Japanese university students, and hafu themselves. Diss. College of Humanities, University of Utah, 2014.